When Evil Wears Good Manners

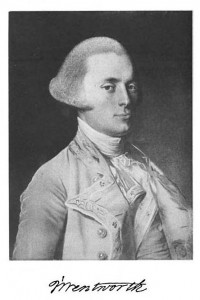

If Courage, New Hampshire, were, well, Courage, Virginia, we might have a more flamboyant royal governor for the show, but this being New Hampshire in 1770, we have one John Wentworth (right) to study, and he’s just that — an interesting study. The enemies of the Wentworth family, in New Hampshire, called his extended kin “The Clan,” and they consolidated their power — right up to the moment that the American Revolution put an end to it –by passing out commissions, land grants, and favors to friends. They were popular people, in other words, and that popularity acted as a brake on revolutionary sentiment.

If Courage, New Hampshire, were, well, Courage, Virginia, we might have a more flamboyant royal governor for the show, but this being New Hampshire in 1770, we have one John Wentworth (right) to study, and he’s just that — an interesting study. The enemies of the Wentworth family, in New Hampshire, called his extended kin “The Clan,” and they consolidated their power — right up to the moment that the American Revolution put an end to it –by passing out commissions, land grants, and favors to friends. They were popular people, in other words, and that popularity acted as a brake on revolutionary sentiment.

“Join the Colony” and Support Intelligent Drama

The young John Wentworth, (just 29 years old when he was commissioned governor) was particularly skillful at appearing cordial to colonials, even as he assured his superiors in England of his zealous attachment to the crown. When it came right down to it, of course, even Wentworth had to make a choice, and that choice eventually sent him scurrying out of Portsmouth and into exile, but during the critical years of 1767 to 1775, he used his personal popularity and calming rhetoric to diffuse the anger that Boston was unleashing on what were then called “the friends of government.”

Behind the scenes, Wentworth lamented a system of government that made every official “from the governor to the constable” dependent on the people themselves. He preferred all government salaries to be issued by London, so as to make the peoples’ overlords independent of those they served. When a road wasn’t built in time to serve his palatial estate at Wolfesborough, he sent dozens of laborers and teams of oxen to finish it, and then presented the offending town with a bill. He didn’t arrest the town leaders, in other words or create any unnecessary drama. He just built his road and concealed the disagreement in an invoice.

New Hampshire, at this time, allowed Congregationalist, Anglican and Baptist worship, and even allowed new townships to pick their denomination, but the separatist tradition of New England meant that the official Church of England was always looked upon with suspicion. No true son of the Pilgrims could ever forget the sort of royally sanctioned, ecclesiastical harassment suffered by the founders of Plimoth plantation, and Wentworth, who longed to establish Anglicanism in New Hampshire as official and “universal” knew it. He had to hide his agenda. Conspiracy, in the present, always seems a little nutty. It only becomes clear, after the letters have been published, and the dirty deeds discovered, sometimes more than a century later.

As the young governor wrote to a friend:

“…However, my dear sir, I cordially venerate the Church of England, and hope to see it universal in this province, whose lasting welfare I have much and sincerely at heart. Whatever is done in this proposed plan must be without parade or show, and under powerful direction, or the whole matter will be injured rather than served…”

John Wentworth to Joseph Harrison, September 24, 1769, as Quoted in Lawrence Shaw Mayo’s, John Wentworth, Governor of New Hampshire

History is full of those who speak their mind and invite confrontation. The real damage is done by those who smile and keep their mouth shut.