Placemen and Pensioners

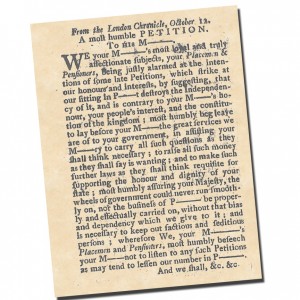

- A London Chronicle Mock Editorial re-printed in the New Hampshire Gazette, January 26, 1770. (Click to read larger version)

The October 12, 1769 edition of the London Chronicle printed a “most humble petition to his M—– [Majesty],” mocking the concerns of “placemen and pensioners.” While most of us know what a “pensioner” might be, you may not have heard of the term “placemen.” It has fallen ouf of use, but it generally meant a royal official who had some sort of nominal duty to perform, but very little accountability for actually performing it. The royal governor of New Hampshire, Benning Wentworth, for example, who served from 1741 to 1766, also held the post of surveyor of his majesty’s forests, at a wage of £300 a year. There is not much record of him doing very much on that score, except collect the royal wage. He was “placed” into position, and enjoyed the benefits, but, like thousands of other “placemen,” he didn’t feel the slightest obligation to justify his earnings.

This reality eventually found its way into our Declaration of Independence, as a grievance against King George:

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

The sons of liberty, if their newspapers are to be believed, were more than aware of the corrupting influence “pensions and places” had on parliament itself. Members of parliament, who were supposed to be paid solely by their constituents, often enjoyed additional “places” and “pensions” from the crown itself, and it doesn’t take an Aristotle to predict how those placemen and pensioners voted, when crown interests were made known.

In May of 1769, the Boston representatives to the Massachusetts general assembly (James Otis, Thomas Cushing, Samuel Adams and John Hancock) were given written instructions from their constituents as follows:

”..it is unnecessary for us at this time, to repeat our well known sentiments concerning the revenue, which is continually levied upon us, to our great distress, and for no other end than to support a great number of very unnecessary placemen and pensioners..”

On May 18, 1770, the New Hampshire Gazette reported:

It has been observed, that though the Civil List consists of £800,000, net money, paid by the Public for the maintenance of his majesty and his family, yet at least £280,000 of this money is yearly seized upon by the ministers, and appropriated in pensions and bribes for the service of their infamous measures; and to writers, for libels on the lords and gentlemen in opposition, and on the people, and the Constitution. But if any men publishes a libel upon the minister, or addresses TRUTH to his SOVEREIGN, he is instantly prosecuted.

Dr. Samuel Johnson, an 18th century literary titan who wrote tracts critical of the American Revolution, was one of these writers who received a crown pension. He was also famous for coining that oft-repeated phrase “patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel.”

Dr. Samuel Johnson, an 18th century literary titan who wrote tracts critical of the American Revolution, was one of these writers who received a crown pension. He was also famous for coining that oft-repeated phrase “patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel.”

He forgot to come clean, though, with what was certainly a much more primary sentiment of his day: “Patriotism may be the last resort of a scoundrel, but a pension certainly is the first.”