Next Episode: Solidarity and Secrets

Revolutions aren’t fought by hoping for the best in people.

In that final stretch leading to the American Revolution, from 1770 to 1775, there were certain conversations that had to be conducted in secret. Certain friendships had to be sealed with something very much like a solemn oath. The largely peaceful pattern we have of elections in this country and our commitment to an orderly hearing of all sides was purchased by people who, for the sake of the cause, had to be absolutely intolerant of deviation from the course.

Think about it: In 1772, when a British revenue schooner, the Gaspee, was boarding coastal vessels, abusing their crews, stealing their merchandise, and mocking due process, the hundreds of Rhode Island men who boarded and destroyed the ship were so silent about the affair that a British investigation couldn’t find one credible witness to point a finger. The inquiry came to absolutely nothing. Imagine that — hundreds of men involved in what would today be called a crime against government property and an assault on government officials, and no one mentions a word about it. Then as now, the investigators had the power to offer inducements of all sorts to testify and no one came forward.

The tea party itself was a marvel of such secrecy that even today, we can’t be sure who participated. Many of those men took the secret to their graves, even after they became victors in the ultimate struggle. The oath of secrecy they took was more important than the free drinks they might have enjoyed the rest of their lives.

This secrecy was in service to a collective virtue that was even more important in securing the victory: solidarity, unity, singleness of purpose. As I wrote a few weeks ago, when a citizen of Cape Anne turned informer, his life became very uncomfortable indeed. When the God-given rights were at stake, and when the debate was finished, there wasn’t much room for waning attention to duty. It wasn’t like signing a boycott agreement and then determining your own standard of purity. You were in, or you were out. My sense is that they had a pretty healthy sense of man’s depravity, and they weren’t above shunning and shaming a fellow soldier into submission.

From this vantage point, some of this makes us uncomfortable. If a group of your neighbors were to show up on your doorstep and say, in effect, “are you with us or against us?” you might think “do I really have to get involved?” Well, in the era leading up to the American Revolution, there was no choice. Life was very difficult for those who couldn’t decide. Today we make a daily virtue out of “live and let live,” and that works, then as now, for many of life’s questions. But suppose you actually saw a magistrate utterly abuse his authority? Suppose you saw your neighbors’ property confiscated without due process? Suppose you were actually there when Stalin’s goons pushed farmers off their land? Wouldn’t utter, black and white polarity, among neighbors, be a useful thing?

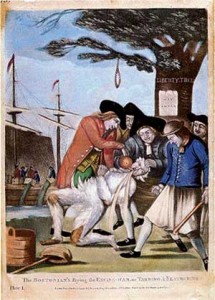

Certainly, it’s an uncomfortable question in the present, but in this age of clean, orderly debate, public hearings, and anemic, non-controversial church life, some folks get a little anxious seeing the founding fathers standing over a barrel of tar and a next to a bag of feathers.

Well, I have news for you: they were harder, meaner men than you might think, when the occasion required it.