“So Spirited A People as the Americans” New Hampshire June 1770

Taking note of what the good citizens of New Hampshire were reading in the summer of 1770.

Taking note of what the good citizens of New Hampshire were reading in the summer of 1770.

The Boston Massacre

On June 29, 1770, the New Hampshire Gazette reported that London papers had just arrived in Boston. The news of the Boston Massacre arrived in England on the 22nd of April, (48 days after the event). In response to the tragedy in Boston, the Secretary of State for the Colonies met with Governor Barnard (then present in London) for three hours. Subsequently, the London papers printed the account of Captain Thomas Preston, who was in command of the troops that fired on the town.

A few highlights of Captain Preston’s account:

“..It is matter of too great Notoriety to need any Proofs, that the arrival of his Majesty’s Troops in Boston was extremely obnoxious to it’s (sic) Inhabitants. They have ever used all means in their power to weaken the Regiments, and to bring them into Contempt, by promoting and aiding Desertions..”

“..one of their Justices..openly and publicly..declared, ‘that the Soldiers must now take Care of themselves, nor trust too much to their Arms, for they were but a Handful; that the Inhabitants carried Weapons concealed under their Cloaths, and would destroy them in a Moment if they pleased..”

“..This, as I was Captain of the Day, occasioned my repairing immediately to the Main Guard. In my way there I saw the people in great commotion and heard them use the most cruel and horrid threats against the troops. In a few minutes after I reached the Guard, about an hundred people passed it, and went towards the Custom-House where the King’s money is lodged. They immediately surrounded the Sentinel posted there..”

“…[after the troops fired on the town]..A Council was immediately called, on the breaking up of which three justices met, and issued a Warrant to apprehend me and eight soldiers. On hearing of this Procedure, I instantly went to the Sheriff and surrendered myself, though for the space of 4 hours I had it in my power to have made my escape, which I most undoubtedly should have attempted, and could have easily executed, had I been the least conscious of any Guilt..”

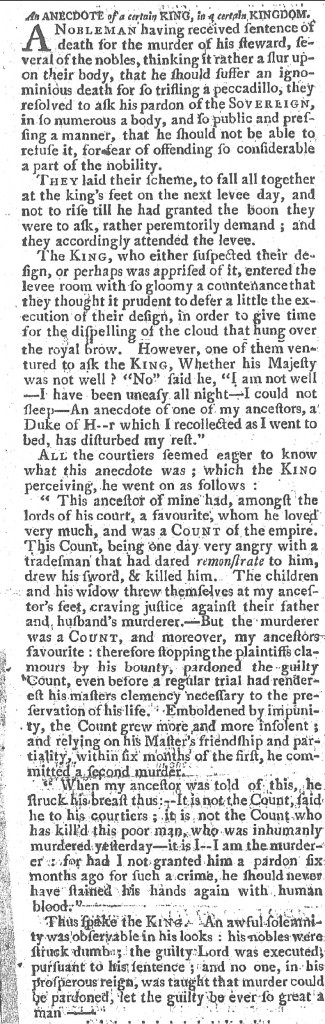

This edition of the Gazette devoted its entire front page to exploring how parliament viewed what they called “the recent disturbance in Boston,” (the Boston Massacre). Of particular note is a debate over  what we would now call classified information. Accounts of Boston had been received by British officers stationed in the town, and in a previous dispute parliament made public note of their names. As the Gazette says of parliament’s deliberations: “General M——cky recommended to the House to be satisfied with a Narrative of the Affairs of Boston, that the King’s faithful Officers there should not be exposed and discouraged from giving accounts, as it was their duty from Time to Time to furnish to Government–That exposing their Letters in the last Sessions was cruel–and if again practiced would prevent any intelligence from thence—that already many avoided writing, and that such as did write were exceedingly cautious therein.”

what we would now call classified information. Accounts of Boston had been received by British officers stationed in the town, and in a previous dispute parliament made public note of their names. As the Gazette says of parliament’s deliberations: “General M——cky recommended to the House to be satisfied with a Narrative of the Affairs of Boston, that the King’s faithful Officers there should not be exposed and discouraged from giving accounts, as it was their duty from Time to Time to furnish to Government–That exposing their Letters in the last Sessions was cruel–and if again practiced would prevent any intelligence from thence—that already many avoided writing, and that such as did write were exceedingly cautious therein.”

Another report: “..A patriotic Nobleman, in a late conference with a Great Personage on the Affairs of Boston, told his Majesty, “That he feared what would be the Consequence when the Soldiers were set, like task-masters, over so spirited a people as the Americans, whose loyalty he held unquestionable, and whose bravery was equalled by none but Englishmen.”

One aspect of the Massacre seemed very prominent in British accounts of the struggle: Captain Preston and others, on the British side of the controversy, claimed that vast numbers of country militia were preparing to march into the city of Boston and use force of arms to compel the 14th and 29th (British) regiments to leave the town. These reports put the number of American troops ready to fight at between 4,000 and 10,000 soldiers, including men who were “..of the first property, character and distinction.”

By the summer of 1770, from the colonials’ perspective, it was clear that Britian had suffered an embarrasing consequence of the massacre. They considered British troops in Boston now to be prisoners of war, held at bay by the colonials themselves.

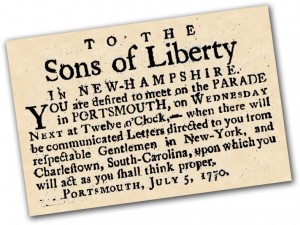

The Non-Importation Agreement

Parliament, in one of history’s great ironies, began considering the repeal of the Townshend duties on March 5, 1770 — the day of the Boston Massacre. The repeal, however, was only partial and still included provisions for making royal governors financially independent of colonial assemblies. A tax would still be laid on tea as well. By the summer of 1770, the various provinces were debating whether to boycott everything produced in Britain or just those items on which a duty was imposed. When Philadelphia reported that Newport (Rhode Island) merchants were breaking the non-importation agreement, the towns of NewCastle, Wilmington and Chester agreed to have “no dealings with them.” It was a hot summer for the non-importation agreement. According to a New York correspondent: “..I am of opinion, that it is in the power of Boston and Philadelphia, to prevent bloodshed in this City, as there are a considerable number who declare they will have recourse to the sword, before they will suffer the [non-importation] agreement to be broke. For my own part, I should think myself a fool, to take up arms to oppose an invasion of a foreign enemy, after submitting to be enslaved by my Fellow Citizens.”

Tar and Feather

In Boston one “McMaster” (a customs official?) was put into a cart with a barrel of tar and a bag of feathers, so as to scare him, and carted over the Boston line to Roxbury. Of interest, perhaps in relation to a Courage episode, is that some of the king’s servants who collected the hated duties, were denied lodging wherever they went.