Between Comedy and Horror

Careful out there in the middle..

I remember enough about mathematics and physics to know that you can be solving for both sides of a complicated equation only to find yourself, miserably, winding down to the painfully obvious. You see it a few steps before the eraser reveals it on paper: a=a.

I’m not sure if I’m on track to the obvious here, but I want to think it through, for the sake, if nothing else, of our relativistic present:

Whether you’re a believer or not, we joke about wrong-doing all the time. We slide right up to it and touch the glassy surface. Believers think of wrong-doing as “sin.” Non believers might see it as a violation of generally accepted standards of behavior. We joke about a friend’s mistake, (“what was he smoking when he said that?”) We go on diets, and generally keep them, but we stuff down a half-stack of Oreo cookies, knowing that we aren’t going off the reservation, just toying with escape. Some wives flirt with the wrong husbands, (and vice versa) and then laugh it off as a joke. The Christian youth minister, before a fireside chat on drug abuse, walks into the chapel and gets a big laugh when he says “sorry, I’m late, I was just snorting a few lines in the bathroom.”

Life would be almost unbearably suffocating without taking a comic look at our constraints from time to time, but sometimes that very comedy can make a transition to moral ambiguity easier. And moral ambiguity can lead to the anarchic embrace of the opposite standard, the one we formerly abhorred. It’s not too difficult to imagine two stock brokers joking about a Ponzi scheme, then wondering at how easy it would be to pull off on a small scale, and then enlarging their wrong doing beyond repair, even defending it. We don’t get fat overnight. We laugh at our weakness, and then we embrace it, and then we defend it like a big cat chasing off hyenas after a kill.

What is adolescence, really, but a desire to do the wrong thing by pretending it’s all just a big joke?

This may be an elaborate way of saying there’s a time to be serious. Have you ever followed an internet debate between a serious, but comedy-challenged combatant and someone who doesn’t know the material but dances around it all, making hilarious sport? Our temptation is to think the comic won the debate, and it might seem that way, but most of us wouldn’t feel comfortable getting advice from Steven Colbert. Even if he managed to say something sober and solemn and wise, we wouldn’t trust the period at the end of his sentence. We would feel the punch line hanging in the air above us.

Sometimes I think that’s the description of the modern condition, a kind of devotion to the comic present. If we can take safe sanctuary in an absurd distraction, we never have to take responsibility for not staying on the diet, for having slipped into an improper relationship, for gossiping about a neighbor, for being cruel, for playing with someone’s affection. We can pretend it’s all a joke and anyone who disagrees is just humorless–and judgmental.

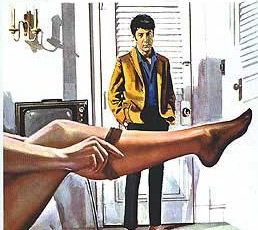

It’s a dangerous emotional territory to guard. Some people can slip around on this wet floor and keep their footing, but whether this mental space is defined primarily by comic distraction or moral ambiguity or just a failure to think, most of our worst decisions are made here in this spot. Your son knows, for example, he’ll be tempted to do something wrong if he keeps company with his date after midnight, but he concentrates on your comic concern for him — and sure enough he gets himself in trouble. You left the house unlocked and at first you see clearly enough to turn the car around, but then someone says, chuckling, “well, I’m sure someone is just going to break in there and burn the place down.” The comic dismissal makes your own concerns seem trivial; you ignore them, and sure enough, your sanctuary is violated. How does the middle aged seductress do it with Ben, when he makes his accusation, “Mrs. Robinson, you’re trying to seduce me?” She laughs. It’s a joke. Of course, it’s a joke.

But it’s also the truth.

It’s as old as the garden of Eden. Introduce confusion, a sense of the absurd, a fogginess about the truth. What does the serpent ask Eve? “Did God really say that?” You could chalk this one up to the benefits of confusion, but I would wager the serpent was also laughing when he made his pitch.

I’m very cautious to make something clear in all of this: you do need a little confusion from time to time and certainly you need to laugh — a lot. I sense something seriously evil in people who can’t laugh, and I know that questioning the premise, indulging enough confusion to keep your mind open, is important. But you can only laugh at a storm for so long. Eventually, you need to drop the sails and batten down the hatches and steer for home, rowing hard if you have to.

The character who realizes this truth in drama will be in danger for his life. The middle ground is the sleepy, foggy, floating territory and people hate the guy who wakes them up. Do you ever hear anyone say “follow me” any more in drama? Without apologizing? It would be something like rushing into a room full of laughing drunks, and shouting, “get serious!”

The character who realizes this truth in drama will be in danger for his life. The middle ground is the sleepy, foggy, floating territory and people hate the guy who wakes them up. Do you ever hear anyone say “follow me” any more in drama? Without apologizing? It would be something like rushing into a room full of laughing drunks, and shouting, “get serious!”

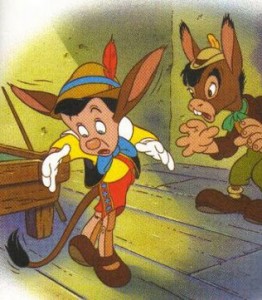

Back to my equation, I wonder if this why drama has lost its edge. The storm–the danger, the sin, the wrongdoing–is never credible, because it has been made into a comic object, or it is a danger totally external to human choice. Yes, a werewolf is frightening, but isn’t becoming a werewolf even more frightening? Wasn’t that the most bone-chilling scene in Pinnochio, when the lost boys were growing tails and beginning to bray like donkeys?

A different generation saw it as damnation, and if it ever becomes comic, heaven and hell disappear for life, and from drama — and then become suddenly, fearfully, real.

…so that’s the equation revealed. It’s obvious, but not so obvious: be careful out there in the middle, boys.