An ‘Encouraging’ Dose of Tar and Feather

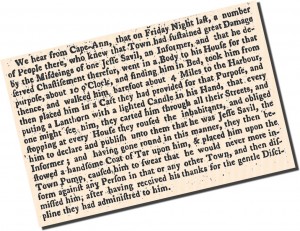

The Tarring and Feathering of Jeffe Savil as reported in the New Hampshire Gazette March 30, 1770 (Click graphic for lager version)

‘Community’ may be many things to many people, but for most of the industrial era, at least, it hasn’t had much to do with seeking justice. The days of the sheriff calling out the posse and deputizing every honest man in the neighborhood have morphed into ‘community watch’ programs, where people just peer out their windows and call in strange behavior. If you conduct an actual citizens arrest, these days, the odds are you’ll either be arrested yourself or wind up under observation . The old right of being able to confront your accuser has migrated into something quite different: the right to accuse anyone anonymously. The fearful task of serving as a witness against violent criminals is now considered so heroic a virtue that entire bureaucracies are dedicated to “witness protection.”

The whole business of processing criminals is now the work of specialists.

Laws that made it illegal for New Englanders to build their own plating mills? Laws that forced New Englanders to buy expensive British West Indies molasses over the cheaper French variety? Revenue captains who could board any ship without a warrant, seize it on suspicion of a violation? Admiralty court judges who were paid a percentage of the cargoes they seized?

To New Englanders, calling these laws ‘unpopular’ would have seemed something like the blithering understatement of a half-wit. More properly, they were seen as ‘evil,’ even if that term wasn’t always used. New England whigs had deferred to them for so long, they were forced to acknowledge their reality as precedents, even if they broke them, over and over again, without the slightest pains of conscience. A law that went into effect without the consent of the governed, and a law that was clearly intended to benefit not the body politic but a favored constituency was the very definition of corruption. So the enforcers of such a law, by Congregational reckoning, were violating their obligation as just Christian magistrates. Informers, people who took money from customs officials for reporting trade violations, were seen as enemies of the community.

In this particular instance, when the traders of Cape Ann faced the wrath of the customs house, by virtue of information turned over by one Jeffe Savil, the town responded by waking the man up at 10 PM, walking him barefoot four miles down to the harbor and then carting him from house to house, where he was obliged to “declare and publish” his name and status. (“Jeffe Savil”, “Informer”). He was then furnished with a “handsome Coat of Tar” and obliged to thank his fellow citizens for their “gentle discipline.” Imagine the sound of the cart wheels turning, doors being beaten open, families stirred from their slumber, and then a prodded shout of confession in the night: “I am Jeffe Sevil. I am an informer.”

Certainly, this is one instance of history being far more entertaining, and instructive, than any reality show, but before we dismiss it all as vigilantism, let’s remember the most effective fighting front against terrorists on the occasion of September 11th. It wasn’t our expensive fighter squadrons. It wasn’t our Cost Guard or our expensive intelligence community.

It was our citizens, the ones who shouted “let’s roll.”